- PII

- S032150750004072-1-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032150750004072-1

- Publication type

- Article

- Status

- Published

- Authors

- Volume/ Edition

- Volume / Issue 3

- Pages

- 53-58

- Abstract

Just over 5 million migrants were permanently registered in the OECD countries in 2017, according to the latest estimates. For the first time since 2011, these inflows are down (around -5% compared to 2016). This is due to a significant reduction in the number of refugees in 2017 while the other categories of migration remained stable or increased [11]. The relationship between international migration and globalization generally is presented in incomplete and simplified way. Very often it does not address globalization in all its complexity, but focuses on a part of the phenomenon or a single point of view, such as the relationship between global economic growth and intensification of international migration. These problems make it difficult to embrace in all its fullness the question, yet they are a good starting point because they concern impacts, dimensions and magnitudes of globalization. Globalization is also accompanied by a concentration of economic activities in major regions of developed countries and some emerging countries. Thus, it is necessary to speak of the fears aroused in the host countries by job losses and the cultural transformations attributed to globalization. One of the five components of globalization often omitted from the analyses of migration is of skilled or low-skilled workers. The purpose of this article is to redefine this complex problem, including various aspects of globalization and their effects, which are often contradictory.

- Keywords

- international migration, globalization, immigration, international organizations, clandestine migration, economics

- Date of publication

- 27.03.2019

- Year of publication

- 2019

- Number of purchasers

- 90

- Views

- 2002

In all the continents of the world, international organizations, research, theories and political analyses that can shed light on the phenomenon of international migration are of great interest and are becoming increasingly important. The growing importance given to this theme reveals the seriousness of the issues it covers for the countries of the world-rich or poor.

International migration requires developed countries to be well prepared. While the demand for foreign labour is rising to offset the effects of falling fertility rates below the replacement level, aging populations and shortages of young workers, their populations are worried about more and more cultural changes that could result in an influx of immigrants, asylum seekers and irregular migrants. Often feared (due to lower wages, unemployment, etc.), the impact of migration on destination countries proves difficult to assess, because it often has indirect and staggered effects over time.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MIGRATION AND GLOBALIZATION

Migration is by far the prelude to globalization; it is consubstantial with the history of humanity. In Western countries, the fear of the events of 11 September 2001 [14] links migrants to terrorist attacks to stir up distrust of foreigners, especially foreigners from less developed countries. Hence the paradox of rich countries: their economy needs immigrant labor, but they are constrained by political pressures and often tend to limit immigration.

The forms and modalities of current migration also have their history. Here are some elements that structure the global migration system: 1) refugees due to wars or natural disasters; 2) economic migration; 3) family reunification; 4) brain drain, technical assistance; 5) the new globalized ruling class (large corporations, international institutions, financial institutions, media, etc.).

But while migration has been rooted in the past, it is also historically located. Today, they are part of the neoliberal phase of globalization. Migration is strongly driven by neo-liberal policies that subordinate growth to the global market.

International migration is also creating pressure in the newly industrialized countries of Asia and Latin America. Many have experienced an accelerated decline in fertility rates in the population. Middle-income countries lose skilled labour, which is due to the persistent migration to the richest industrialized countries, not without benefit (or inconvenience) from this exodus, partly offset by the money migrants sent to their families and communities.

The poorest countries are not spared from the conflicting pressures engendered by international migration. The living conditions that prevail there encourage many of their inhabitants (mostly young people) to immigrate to a richer country, although they do not always have most of the skills, the qualification and the required finances to be legally admitted and to settle successfully. Therefore, migration from poor countries is often clandestine and poorly enumerated. These migrants in search of better living conditions find themselves at the mercy of employers and subjected to be considered criminals in the eyes of the police, which generates a migrant market.

The geographer Gildas Simon analysed the «perverse effects of the hardening of admission policies in the European Union and North America». According to him, «real underground markets for migration have thus been created», obstacles resulting in higher costs for illegal «travel». To come to France when you are Chinese, you need from 10,000 to 20,000 euros: a «package» including a «package of services» [17].

The migration economy was also highlighted by political scientist Catherine de Wenden. She said that the price of the crossing of the Mediterranean, from Tunisia to Italy, can reach 1,500 euros, while the crossing of the border between Mexico and the United States is estimated at $3,000. In the European Union, «this saving of the passage releases 4 bln euros in profits per year» [23]. From these two points of view, we can understand that the tightening of migration policies in rich countries leads to poorly controlled and non-oriented migration.

It is no secret that these developments in international migration and immigration policies are linked to a global process of economic, cultural and political transformation commonly referred to as globalization. Evidence of their economic impact follows. In 2017, the World Bank estimated that official remittances to developing countries amounted to $429 bln in 2016, a decrease of 2,4% compared to 2015, when they totaled more than $440 bln. If we also include shipments to highincome countries, total global transfers fell by 1,2% in 2016 to $575 bln, compared to $582 bln in 2015 [19].

Remittances are an important source of income for millions of families in developing countries. As such, a weakening of remittance flows can have a serious impact on the ability of families to get health care, education or proper nutrition. Refugee flows play a specific role in specialized work to analyse the economic impact of immigration. Because of the involuntary nature of these flows, they can sometimes be an exogenous source of variation in the level of immigration in space or time [2; 4].

One of the main results of OECD analyses reveals that humanitarian migrant flows generally have only a negative impact on the labor market outcomes of the native-born, or even no impact at all. However, some studies have identified more significant negative effects, while other studies have established that the complementary skills of refugees and persons born in the country can have a positive impact on the latter [13].

RECENT LITERATURE

A research by Alan Simmons in the field of migration is a pioneering document, to the extent that he aims to put in order the definitions and typologies and, above all, to place migratory theories in their historical contexts [15]. He suggests three parameters as a basis for defining migration: change of residence, change of employment and change of social relations. In general, migration is defined essentially according to the first criterion, namely the change of residence. Simmons’ innovative suggestion to expand its definition will become increasingly relevant, particularly in research focusing on macro-structural factors [16].

In much of their current work, theorists and researchers in international migration do not explicitly integrate globalization as a concept. Many recent theoretical models treat it as a non-pertinent issue, or somehow outside the frame of scrutinized issues. A researcher can reasonably neglect globalization [1; 5; 6]. Thus, a theory of migrant decision-making may be based on a model of the expected results of migration likely to apply in any historical or social situation.

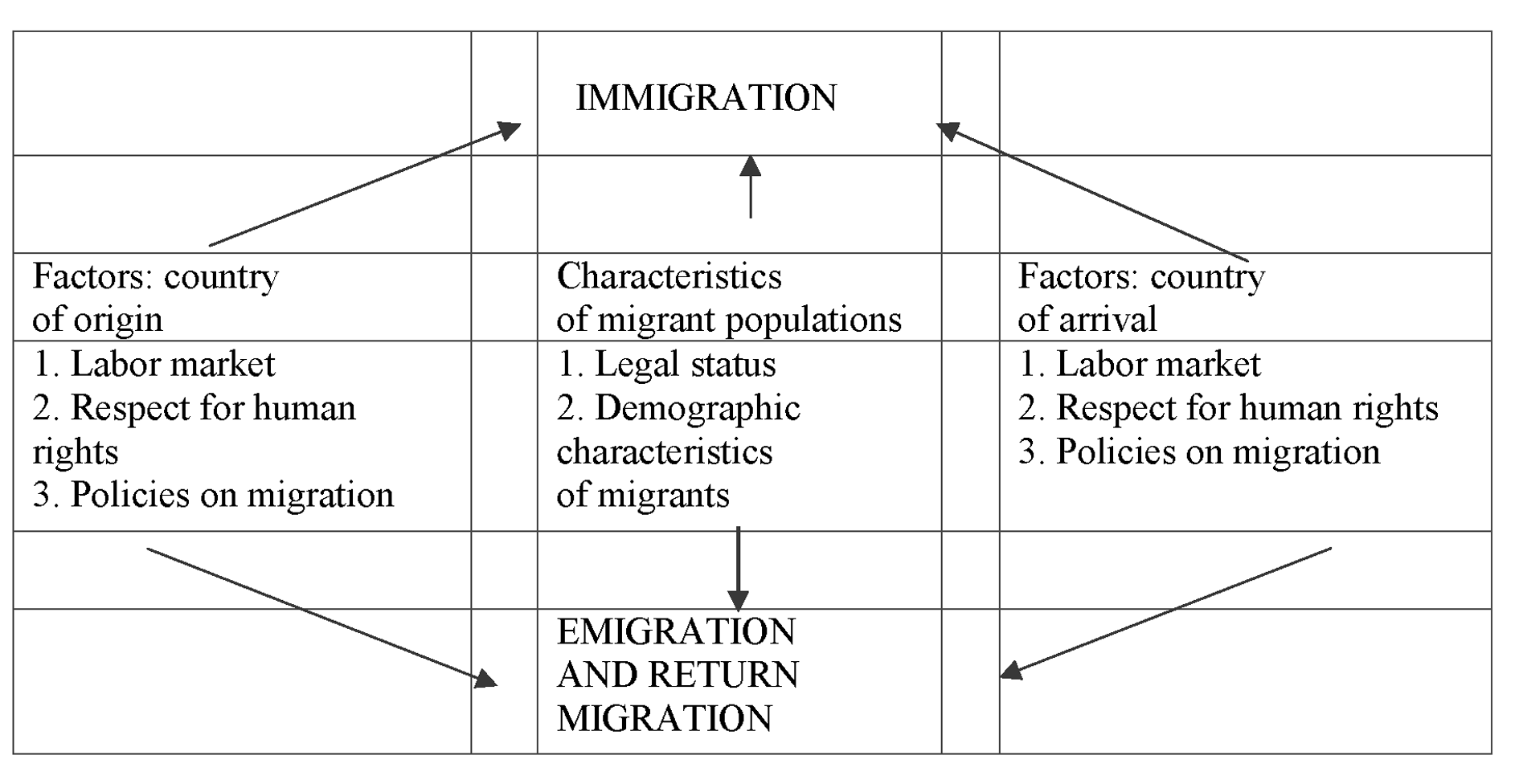

The analysis proposed by the historian Philip Mus shown in Figure 2 is an example of the inscription of migratory systems in a macroscopic model integrating certain elements of the globalization without taking this one as point of the approach [8].

The model draws attention to various current aspects of labour demand in rich countries, poverty in developing countries, and other factors of attraction or repulsion, which are included as a gear of the international migration regime. The Mus model almost always treats the specific determinants of international migration it incorporates as if they were independent of each other. In other words, the elements of the model are weakly integrated. This is the pitfall that we want to avoid by proposing to take the role of globalization as a framework for the analysis of links, sometimes involving contradictory influences between the socio-economic and political macro-determinants of international migration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Systemic presentation of the factors shaping international migration.

Source: [8].

In today’s work, the systemic models of globalization remain incomplete and unfinished. Take the example of two books that identify globalization as a starting point for analysing trends and policy issues in international migration.

Peter Stalker’s book Workers Without Frontiers: The Impact of Globalization on International Migration [18] deals primarily with the globalization of trade and economic output, and addresses international migration about arbitrage movement of workers to overseas production sites and travel facilities to the countries where the workers live.

As far as the cultural and political dimensions of globalization and its links to international migration are concerned, P.Stalker only speaks of it very briefly, in a few introductory paragraphs devoted to global consciousness and, later, in a section on «political disturbances» related to the impact of the abolition of trade borders and the acceleration of capital movements on job losses and workforce adjustment, particularly in poor countries. Stalker is aware that much of globalization is shaping the face of international migration through these mechanisms, but it is not part of his approach and he does not stop there. But the issue needs to be broadened to pay more attention to the cultural and political dimensions of globalization [18].

There is an approach to globalization that overlaps that of Stalker in the work of A.Stephen Castles and Mark J.Miller The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World [5], with a focus on slightly different aspects. By giving more space to culture, this work also gives more attention to issues of racism, ethnocentrism and unequal integration of migrants in host societies. In generally, Castles’ approach is among the most complex and promising, particularly because it highlights the contradictory forces at work in the context of globalization today.

In short, globalization has become the key word in the research and theories on international migration, but recently it has been driven by quite different problems. In the rest of this article we will examine some data of international organizations on international migration and refugee movements that illustrate the trends observed in recent decades, during which the current phenomenon of globalization has unfolded.

GLOBAL TRENDS OBSERVED

The changing image of major trends in international migration makes it difficult to formulate issues that integrate globalization and international migration. Among the global trends observed in the world of employment, which ones are important to take into consideration in carrying out this modelling effort? Some were selected: what are the facts concerning them?

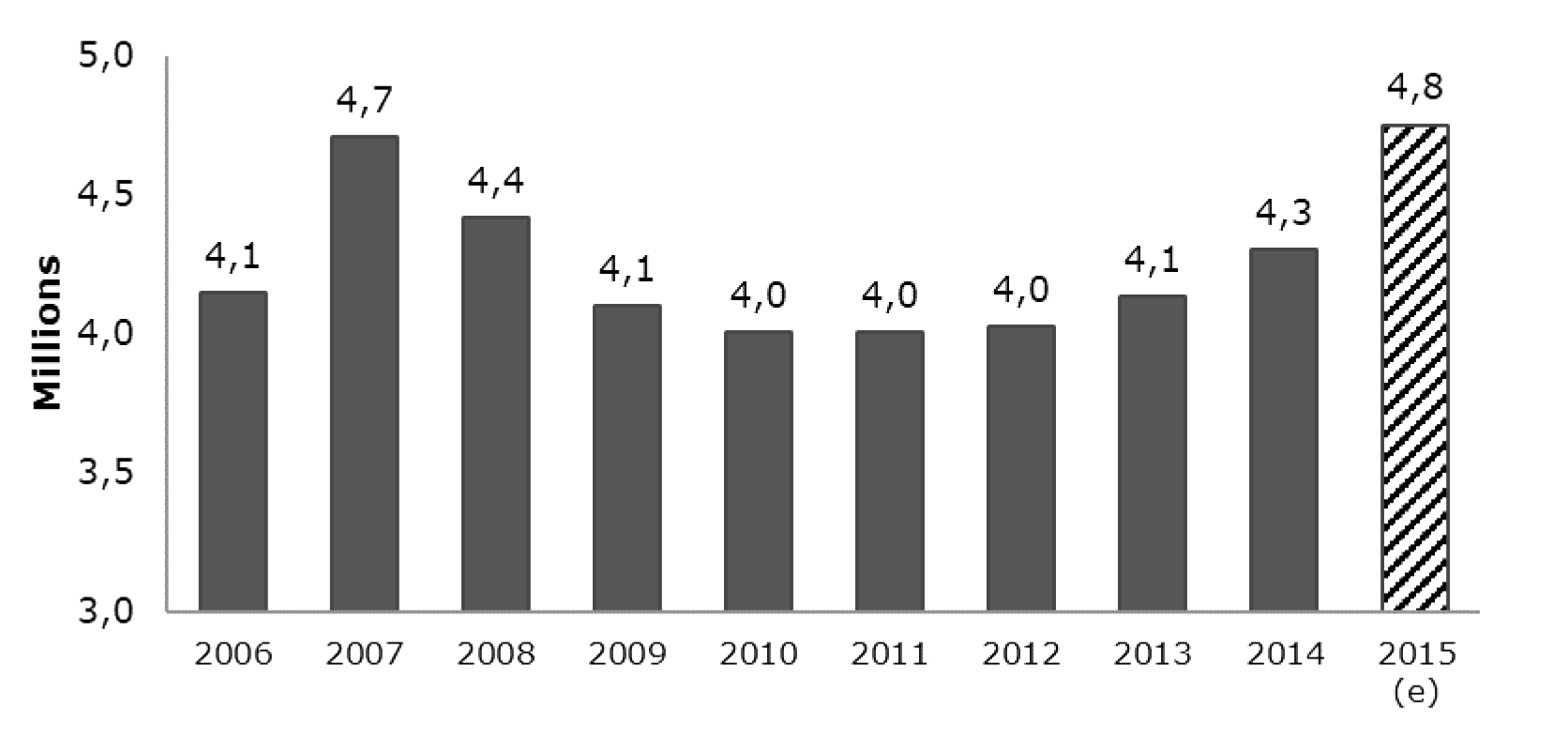

Figure 2. Permanent entries in OECD countries, 2006-2015*.

* Data from 2006 to 2014 are the sum of standardized data for the countries for which they are available (this represents 95% of total entries in OECD countries) as well as non-standardized data for other countries. The 2015 data are estimated based on the growth rates published in the official national statistics.

Source: [10].

1. Increasing migration flows: a reality?

There is the idea that globalization will tend to amplify ever more the movement of people between countries. It is to consider one side of the issue, forgetting that globalization also generates in the host countries cultural, political and economic insecurities (fear of job losses, etc.) that lead them to tighten their borders. The world is characterized by a contradiction more and more marked by the pressures that drive mobility intensification, border controls and the rejection of foreigners reduce. These two opposing tendencies can be accentuated by various aspects of the same process of globalization.

If we go by the overall global trend expressed by the available data on international migration flows, preliminary data indicates that generally flows in the countries of the OECD were at the highest level in 2015 with 4.8 mln new permanent entries representing a 10% increase compared to 2014 (Figure 2).

However, in 2017, just over 5 mln permanent entries were recorded according to the latest estimates revealed in the report International Migration Outlook 2018 published by the organization. For the first time since 2011, this figure is down, and it is about -5% compared to 2016. This is explained, according to the OECD report, by a significant decrease in the number of recognized refugees [13]. This is to say that we are mistaken in thinking that international migration increases with globalization, at least on a global scale. This does not mean that the global trend coincides with what is happening in all countries.

Migrants to Europe and to countries with predominantly European populations are not of European origin. They come from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America. In many host countries, it is inferred that immigration is increasing, but in reality, it is the visibility of the cultures and ethnic origins of immigrants that has changed.

2. The refugees: more and more

The panorama of international migration in recent years has changed profoundly. All regions of the world are now affected and the traditional distinction between host countries, countries of departure and countries of transit is becoming blurred. The profile of migrants also takes many forms because now the migrations involve all the different categories of populations.

In 2017, international migrants numbered 258 mln people, that is, people living in a country other than the one where they were born, reached 244 mln in 2015, an increase of 41% over 2000, according to new statistics presented by the United Nations. This number includes nearly 20 mln refugees, according to the OECD [13].

Much has been said about the many possible impacts of globalization on global refugee flows, believing that changes in global investment and trade, accompanied by rapid changes in exports, production and employment, could trigger or aggravate political unrest, social conflict and repression of dissidents in poor countries [7; 9].

Based on the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees [20], a Convention refugee is a person who, «fearing persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of which he is a national and cannot go back there». Is the number of people applying to this definition increasing worldwide in this wave of globalization? The answer is not obvious. Ethnic conflicts, authoritarian states and poverty are born and die due primarily to historical and regional dynamics specific to each territory. The influence of globalization, in addition to these factors, could have an impact on refugee movements and flows, but this remains a complex issue.

According to available data, the number of displaced persons has reached its highest level. UNHCR’s annual statistical report on global trends reported a record number of 65.6 mln uprooted people around the world at the end of 2016 because of persecution [21]. The seven-year conflict in Syria led to the largest number of refugees in the world (5,5 mln). But in 2016, South Sudan was the new leading factor, as the catastrophic rupture of peace efforts in July led to the departure of 737 400 people before the end of the year and this continued to increase during the first half of 2017 [22]. This huge imbalance reflects several factors including the absence of an international political consensus on the question of the reception of refugees, as well as the increase in its many conflicts’ region and poor countries. Regardless of the angle at which it is examined, these figures are unacceptable.

The slight decline in total refugee populations worldwide in the late 1990s and in 2018 can be explained in part by the end of the cold war in 1991; by the fact, already mentioned, that the host countries have made it more difficult for asylum seekers to enter their territory, and by the increasing number of ethnic conflicts.

This last point seems to be confirmed by the growth in the number of displaced people in the world. These are people who, without leaving their country, were driven from their homes by circumstances of civil war, violence, insecurity, poverty, poor management, which would have been likely to make them flee abroad. These situations have multiplied rapidly around the world, and the number of people affected is so high that the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), expanding its mandate, is now on the alert for this problem and works to solve it.

* * *

Globalization tends to activate international migration, but also the willingness of host countries to control the admission of migrants more closely. Migratory flows develop and reach all countries but drawing sometimes very different configurations. More and more, rich countries are attracting migrants from all parts of the globe, especially those from poor countries.

The latter undertake journeys farther than before because, in search of a country richer than the one from which they come, they meet more and more with a refusal, which forces them to the clandestine migration, which is not registered. Globalization creates a desire for people seeking asylum to move to other countries for protection, but it also creates a system of rules and restrictions that impedes migration and holds back many displaced by conflict and civil war. With it, it is likely to increase the smuggling of migrants destined for moonlighting, prostitution to slavery, and forced labour. These and other trends discussed in this article provide insights into the effects of its often conflicting economic, social and political dimensions.

The dimension of globalization can exert conflicting influences on international migration, creating social and political tensions in source countries, migrant families and host countries. Economic globalization encourages migration, but at the same time threatens cultural changes that may encourage host countries to join forces to stem migration through treaties and border control agreements. While the possibility of an increase in international migration crystallizes xenophobic reactions conducive to the emergence of measures to limit it, migration itself generates hybrid identities and tends cultural bridges within and between countries. Inevitably, globalization makes migration a field of contradictions, conflicts and paradoxes.

References

- 1. Afolayan A.A. (2001). Issues and challenges of emigration dynamics in developing countries. International Migration. Pp. 5-38.

- 2. Borjas G., Monras J. (2017). The Labor Market Consequences of Refugee Supply Shocks. Economic Policy. P. 130 – http://ftp.iza.org/dp10212.pdf (accessed 05.10.2018)

- 3. Castles S., Miller M.J. (1998). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern Word. New York: Guilford.

- 4. Clemens M., Hunt J. (2017). The Labor Market Effects of Refugee Waves: Reconciling Conflicting Results. P. 230 – https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/labor-market-effects-refugee-waves-reconciling-conflicting-results.pdf (accessed 15.10.2018)

- 5. Hammar T., Brochmann G., Tomas K., Faist T. (1997). International Migration, Immobility and Development. Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

- 6. Iredale R. (2000). Migration policies for the highly skilled in the Asia-Pacific region. International Migration Review, № 34. Pp. 882-906.

- 7. Massey D., Arango J., Hugo G., Kouaouchi A., Taylor J. (1998). Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- 8. Mus P. (1994). South-to-North Migration in United Nations. Population Distribution and Migration (La Paz, 8-22 January). New York: United Nations Population Division. Pp. 243-258.

- 9. Myers E. (2000). Theories of international immigration policy: A comparative analysis // International Migration Review, № 34.

- 10. Perspectives des migrations internationals 2016 – https://static.mediapart.fr/files/2016/09/16/pdfx-001-456.pdf (accessed 20.08.2018)

- 11. OCDE. International Migration Outlook, 2016 – https://books.google.ru/books?id=Z9YZDQAAQBAJ&pg= PA20&lpg=PA20&dq=Les+donn%C3%A9es+de+2006+%C3%A0+2014+sont+la+somme+des+donn%C3%A9es+standardis %C3%... (accessed 29.08.2018)

- 12. The OECD considers as an immigrant any person living in the host country but born abroad (including «national» parents). This definition differs from that of INSEE (a person born abroad and remaining an immigrant even after having acquired French nationality) – https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1284 (accessed 26.08.2018)

- 13. OECD. International Migration Outlook 2018. Great Trends – https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migrationhealth/international-migration-outlook-2018/summary/english_9fe5b4b8-en#page1 (accessed 20.09.2018)

- 14. September 11, 2001: Attacks on the World Trade Center. Review of both worlds. September 2017 – https://www.revuedesdeuxmondes.fr/11-septembre-2001-attentats-tours-jumelles/ (accessed 20.10.2018)

- 15. Simmons A. (1987). Explaining migration: Theory at the crossroads. Explanation in the Social Sciences: The Search for Causes in Demography. Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium): Catholic University of Louvain, Institute of Demography. Pp. 73-92.

- 16. Simmons A. (1998). Racism and immigration policy. Racism and Social Inequality in Canada. Toronto: Thompson Educational. Pp. 87-114.

- 17. Simon G. (2008). The migratory planet in globalization. Paris: Armand Colin. P. 58.

- 18. Stalker P. (2000). Workers Without Frontiers: The Impact of Globalization on International Migration. London. Pp. 6-8.

- 19. The World Bank. Remittances to Developing Countries Decline for Second Consecutive Year, 2017 – http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/04/21/remittances-to-developing-countries-decline-for-secondconsecutive-year (accessed 08.10.2018)

- 20. UNHCR. Implementation of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees Implementation of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1898 – http://www.unhcr.org/excom/scip/3ae68cbe4/implementation-1951-convention-1967-protocol-relating-statusrefugees.html (accessed 08.10.2018)

- 21. UNHCR. The State of the World’s Refugees: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- 22. UNHCR’s Annual Statistical Report on Global Trends. Geneva, 19 June 2017 – http://www.unhcr.org/ en/news/stories/2017/6/5943f3eca/number-people-located-level-decennies.html (accessed 08.09.2018)

- 23. Wenden C. (2018). Migration Atlas a global balance to invent. London. Pp. 30-40.